For up to three million years, human beings have been working creatively with their environment. The famous Makapansgat Pebble—a small rock featuring a convincing human face—may have been plucked from a stream bed and carried as a talisman as far back as 2,900,000 B.C. The earliest known human drawings, including handprints and hatchmarks, may date to around 70,000 B.C. and possibly earlier. In fact, by about 50,000 B.C., humans were making elaborate imagery—featuring animals, and later, people—all over the world from France to South Africa and from Namibia to Indonesia.

Artworks like these, and the much grander monuments that succeeded them, can tell us volumes about our common human nature. And perhaps, most intriguingly, they show how humans across the ages have intuited the spiritual in similar ways. In my previous posts, I’ve discussed striking global similarities among temples, pilgrimage traditions, and body adornments. In this post, I’ll discuss similarities in global burial traditions. Across eras and continents, humans have created monuments, treasure chambers, and reliquaries as links with the afterlife. Their efforts attest to a universal human understanding about the soul’s immortality and a world beyond our mortal sphere.

Monuments

Since around 5000 B.C., if not earlier, humans across all inhabited continents have been constructing mounds to house their dead. Tens of thousands of these mounds, spanning the world, survive today. Scientists call these majestic but rudimentary structures tumuli (sing. tumulus), and they are built of either piled earth or stone. Famous examples of such early burial mounds include the barrows of England (immortalized in J.R.R. Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings), the 200-foot-tall mound of King Alyattes in Turkey, and the Hopewell mounds of North America. The countryside near Rome, Italy, meanwhile, boasts thousands of haunting tumuli made of massive cut stone, overgrown with moss and containing lavish sculptures and sarcophagi.

_-_panoramio-3.jpg?width=2322&name=Necropoli_cerveteri_(DC)_-_panoramio-3.jpg) Necropoli cerveteri / corinasdavide, CC BY 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons

Necropoli cerveteri / corinasdavide, CC BY 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons

All of these mounds were costly and laborious to construct, and they show ancient humans’ deep reverence for the dead. Some also may have served astronomical purposes, linking the dead with the wider cosmos. But most importantly, in their monumentality, these structures claimed a part of their environment as set apart, sacred or even otherworldly. That’s why anthropologists and art historians call constructions like these “liminal” or “threshold” spaces, marking a transition from one spiritual reality to another. Before an ancient tumulus, our ancestors may have felt connected to a world beyond our own—the realm of eternity.

Naturally, as human technology advanced, human beings’ monuments to the dead increased in size and luxury. Some of the most world-renowned funerary monuments are the great pyramids at Giza, Egypt, that once housed the remains of three generations from one royal family and almost bankrupted the Egyptian empire. These constructions are tumuli on a massive scale, polished and sharpened. The tallest pyramid, dedicated to the pharaoh, King Khufu, stands 455 feet high. As “liminal” objects, the great pyramids possess vast imaginative power, causing observers through the ages to consider them the works of extraterrestrials or gods.

Pyramids of Egypt / Copyrighted free use via Wikimedia Commons

Pyramids of Egypt / Copyrighted free use via Wikimedia Commons

While the great pyramids are among the largest burial monuments in the world, other equally impressive “liminal” tomb structures exist across all continents. In Japan, the Tokugawa Shoguns established elaborate burial shrines, complete with massive earthworks, gardens, and lacquered temples. The ancient Romans built giant cylindrical tombs for their greatest emperors, one of which has been repurposed as today’s Castle of St. Michael. The great architectural complex of Angkor Wat, Cambodia, has the mausoleum of King Suryavarman II at its core. And in Agra, India, the Mughal Shah Jahan built the famous Taj Mahal as a tomb for himself and his favorite wife. Meanwhile, in Central America, archaeologists have discovered evidence of royal burials within pyramid structures to rival those of ancient Egypt. Across the world, such “threshold” constructions have been revered parts of communal life, worthy of tremendous time and expense.

-Aug-19-2021-06-19-27-39-PM.jpg?width=2991&name=India_2015-159_(16957535807)-Aug-19-2021-06-19-27-39-PM.jpg) Taj Majal / Weldon Kennedy from London, UK, CC BY 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons

Taj Majal / Weldon Kennedy from London, UK, CC BY 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons

Treasure Chambers

The grand tomb-monument is an “outward facing” message to the living: a reminder both of departed ancestors and of an eternal realm that waits beyond. Some important tombs, however, have been “inward facing,” secret, and hidden—meant chiefly for the eyes of spirits and gods.

In ancient China, emperors and other powerful figures were often interred inside mountains. Within these tombs, workers crafted entire otherworldly kingdoms for their emperor’s use in the afterlife, even as the tomb’s exterior blended in with its surroundings. A famous example is the tomb of the Qin Emperor at Xi’an, China. Here, about 8,000 terra cotta soldiers stand guard together with sculpted horses and chariots. But they are only the beginning. Further excavations are expected to reveal palaces, towers, and human sacrifices that accompanied the emperor in death. The “inward” orientation of this structure was so total, in fact, that the craftsmen who built it were trapped inside upon its completion. Its secrets were never to be divulged to living eyes.

-1.jpg?width=1286&name=Terra_Cotta_Bodyguard_(5422323744)-1.jpg) Terra Cotta Bodyguards / BFS Man from Webster, TX, USA, CC BY 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Terra Cotta Bodyguards / BFS Man from Webster, TX, USA, CC BY 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons

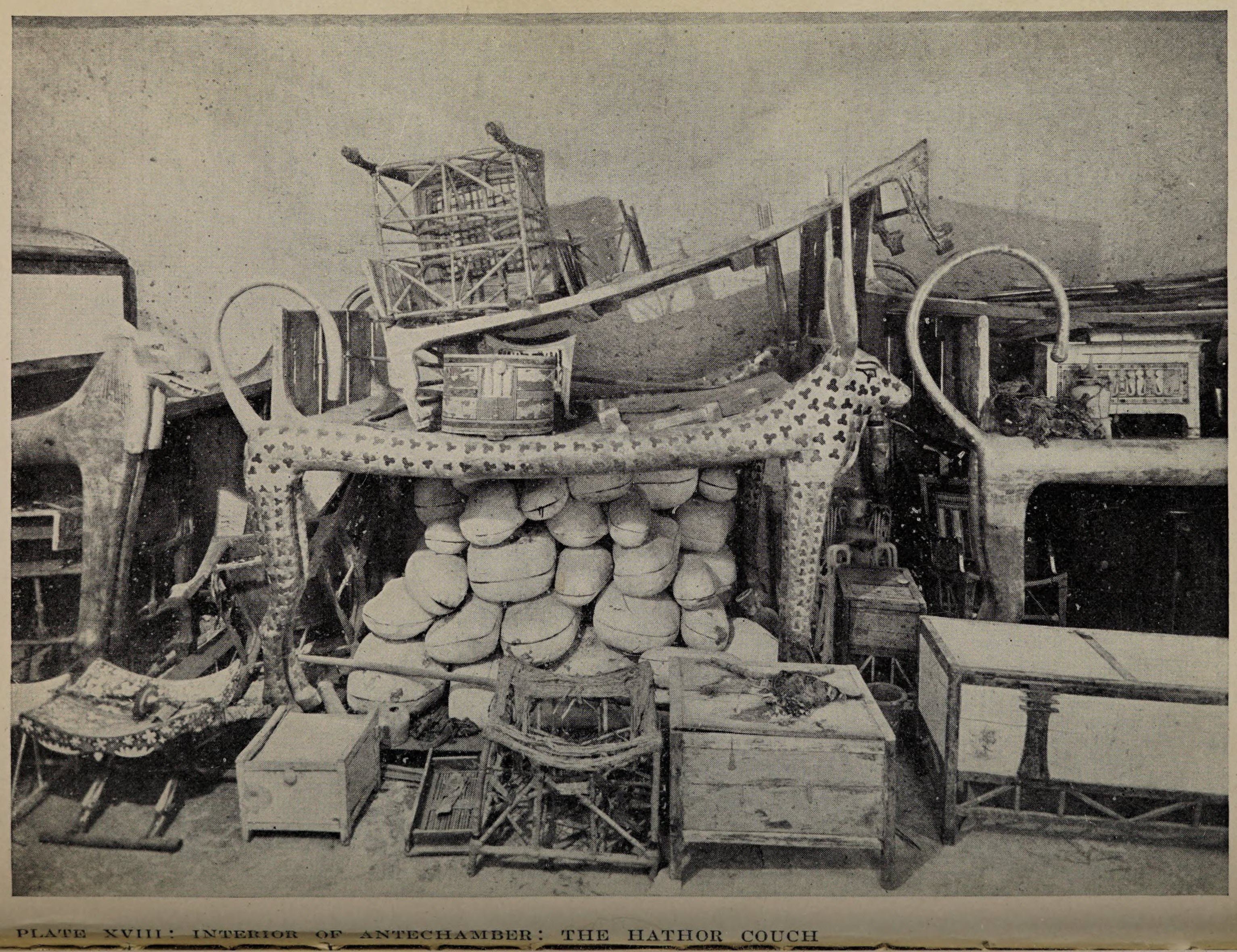

Tombs in the Ancient Middle East and North Africa were also filled with treasures for the afterlife, just like the tomb of the Qin Emperor. In Egypt’s Valley of the Kings, relatively non-descript tombs were excavated from hillsides and stocked with food, clothes, perfumes, medicines, and even vehicles like boats and chariots. The most important funerary equipment in this region, however, was statuary of the deceased. Many ancient peoples of this region believed the soul’s survival depended on the preservation of its earthly image. Accordingly, images of pharaohs and other leaders were carved from the hardest and most durable stone.

Items from the Tomb of Tut-Ankh-Amen / Harry Burton (illustrator & photographer), Public domain

Items from the Tomb of Tut-Ankh-Amen / Harry Burton (illustrator & photographer), Public domain

Finally, in South America, similarly “hidden” treasure-chamber tombs can be found in the cliffs of Peru. These mausoleums, resembling the cliff dwellings of the Southwestern United States, are cut high into the rock face at elevations approaching 10,000 feet. These were the eternal “homes” of Chacapoyan mummies, remarkably well-preserved, and they were likely once stocked with supplies for the afterlife. On a smaller scale, “hidden” treasure burials have been found in places like Sunghir, Russia (dating to around 30,000 B.C.) and in England at Sutton Hoo.

Mausoleos de Revash / PsamatheM, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Mausoleos de Revash / PsamatheM, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Relics and Reliquaries

The burial structure with perhaps the greatest spiritual potency, however, is the reliquary. Relics, or the preserved and venerated remains of ancestors, can include both bodily remains such as bones and blood or remnant possessions such as clothing or weapons. Reliquaries are the structures used to house these objects and can range in size from the small and jewel-like to the architectural and massive. Some relics are kept within lockets; others lie in structures the size of palaces.

In many world cultures, the remains of ancestors have been preserved and enshrined as important liminal objects that maintain a link with the spirit world. These relic-remains are not hidden away but are cared for and handled through rituals that cross thresholds into eternity. In many Asian cultures, for example, ancestors’ bones are exhumed, cleaned, and decorated a few years after their initial burial. They are then moved to new collective tombs where the bones of many relatives are kept together. This ensures family connection in the afterlife. In many African countries, meanwhile, ancestors’ bones are kept in or near the home in large vessels surmounted by sculpted guardian spirits. The bones’ owners are thought to watch over their descendants from their vantage in the world beyond.

Reliquary Guardian Figure Boumba Bwiti / Brooklyn Museum, CC BY 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons

Reliquary Guardian Figure Boumba Bwiti / Brooklyn Museum, CC BY 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons

Relics in Christianity

The global tradition that has prized relics the most, however, may be Roman Catholic Christianity. Beginning at the height of the Roman Empire, with the first Christian persecutions and martyrdoms, early Christians gathered the relics of their fallen heroes and paid them homage. These earliest relics were at first quietly venerated within the massive burial sites called catacombs. Later, after Christianity was legalized, many were disinterred and brought above ground into churches where they were placed in beautiful vessels of gold, silver, and glass.

Reliquary Chasse / Hunt Museum, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Reliquary Chasse / Hunt Museum, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

For early Christians, the liminal, or “threshold” quality of saints’ remains was especially potent. This is because Christians experienced a collapse of the gulf separating history from eternity. They believed their God had become human and they believed he had been resurrected with an eternal physical body that incorporated his mortal one. Since the Christian God had promised a similar resurrection to his true followers, the bodily remains of the Christian dead were understood as “seeds” of something greater and more fruitful. They were paradoxical incubators of a future life that was spiritual and physical all at once. Thus, relics in the ancient Christian traditions have been presented with a brazenness unrivaled by other world traditions, and are often spotlit, gilded or covered with jewels. In these remnants of the holy, tightly connected to the world beyond, one can truly find (it is said) “heaven on earth.”

Arm Reliquary / Metropolitan Museum of Art, CC0, via Wikimedia Commons

Arm Reliquary / Metropolitan Museum of Art, CC0, via Wikimedia Commons

No Mere Mortals

Humans’ global, age-old care for the dead—our determination to lavish time and treasure on monuments to the afterlife—attests to our universal spiritual priorities. In most world cultures, living people have toiled and sacrificed on behalf of the dead, valuing spiritual comfort above the needs of the day-to-day. Their commitments illuminate this observation by the scholar C.S. Lewis:

“There are no ordinary people. You have never talked to a mere mortal. Nations, cultures, arts, civilizations—these are mortal, and their life is to ours as the life of a gnat. But it is immortals whom we joke with, work with, marry, snub and exploit—immortal horrors or everlasting splendors.” —C.S. Lewis

For Lewis (and many of our forebears) one human soul was vastly greater than a whole civilization. If Lewis was correct, then our present focus on fleeting, sensory pleasures (exemplified by multi-billion-dollar industries in junk food and porn), together with our general refusal to confront death and its aftermath, seem ill-conceived. We are squandering our true dignity, and we are denying an onrushing future that will claim us all. Perhaps renewed attention to our common spiritual heritage—both its glories and its telling distortions—can help us recover a better sense of the meaning of life, both mortal and eternal.

Feature Image: Barun Ghosh / copyrighted free use via Unsplash