If art history is any indication, human beings have been deeply spiritual for millennia. And they have expressed their religious impulses in similar ways. In earlier blog posts, I discussed stunning congruencies among objects like tombs, statues, temples, and relics hailing from distant parts of the world. Both North Africa and Central America, for example, have produced grand and mysterious pyramids. Major pilgrimage roads can be found in Europe, the Americas, Asia, and the Middle East. And intriguingly, there are ceremonial mask traditions in places as far distant as North America, South Africa, and Tibet.

One art form, however, is particularly associated with the Christian spiritual tradition and the cultures it has touched. That art form is the small, rectangular picture—now ubiquitous on our desks at work, mantelpieces, and smartphone screens.

Of course most, if not all, human cultures have developed pictures. Indeed, most of the earliest artworks are pictures—either painted onto cave walls or etched into rock. These specimens, dating back tens of thousands of years, can be found in places as far apart as France and Indonesia. Petroglyphs, or rock drawings, seem to have been central to many ancient cultures, and they are still revered in some African and North American communities today.

Horse Petroglyph, Dinosaur National Monument / Bureau of Land Management, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Horse Petroglyph, Dinosaur National Monument / Bureau of Land Management, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

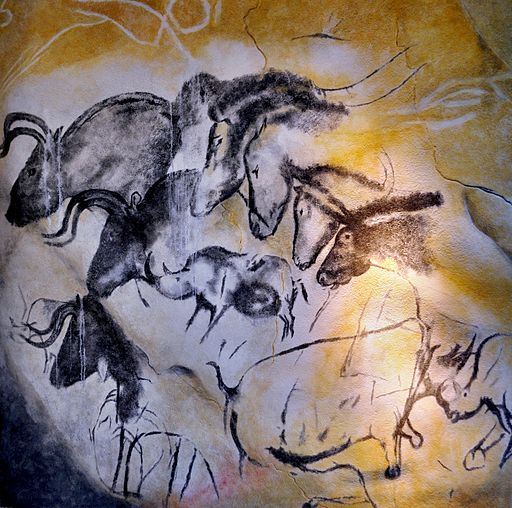

All of these early images show remarkable—almost miraculous—sophistication. Though pictures can be made by simply rubbing charcoal on a rock, the symbolic thinking they require demands marvelous powers of observation and synthesis. No other animal has approached this feat—and arguably, no modern artist has surpassed some of history’s earliest. That is why Pablo Picasso, upon seeing the cave paintings at Lascaux, declared, “we have invented nothing!” Fifteen years earlier, the writer G.K. Chesterton had come to the same, awe-struck conclusion in his book The Everlasting Man.

Etologic horse study, Chauvet cave / Thomas T., CC BY-SA 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Etologic horse study, Chauvet cave / Thomas T., CC BY-SA 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons

But pictures, it seems, have not usually been foci for worship in the same way statues, relics, and monuments have been. Instead, they have been means to an end—parts of a process. They have been maps, mnemonics, or vestigial traces of rituals, moving the faithful onward and then humbly receding into the dark.

Consider, for example, the overlapping animal paintings at Chauvet Cave in France. These paintings, made in a deep cavern, would seldom have been clearly visible; this made them highly unsuitable for worship and contemplation. The painted animals were also copied again and again, with their outlines intersecting and blending in confusing ways. It is likely, therefore, that these images were part of a ritual process aimed toward taming hunting quarry. To inscribe the animal was to master the animal; it was a kind of training in knowledge and power. Here, it seems, the process was more important than the product. Later examples of such “process painting” include Tibetan sand painting and the early Dreamtime images of the Australian Aborigines.

Hevajra Mandala / Wonderlane, CC BY 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Hevajra Mandala / Wonderlane, CC BY 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons

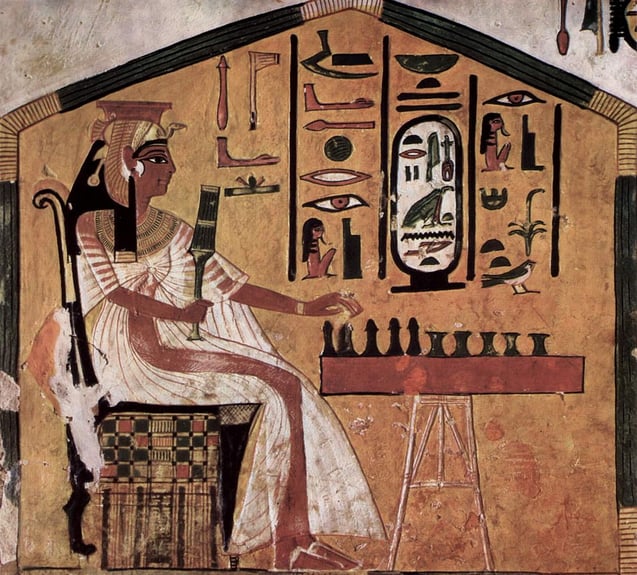

Other early types of painting were instructional, functioning as diagrams for—or illustrations of—important conditions and dynamics. The paintings inside Egyptian tombs are of this genre: never meant for human eyes. These images, interspersed among passages of hieroglyphic text, often map the soul’s progress through the underworld. Similarly diagrammatic, in their different ways, are Buddhist mandalas and the calendrical imagery of the ancient Mayans. These images map out space and time (both earthly and celestial) and mark positions and events with important symbols.

Maler der Grabkammer der Nefertari 003 / Maler der Grabkammer der Nefertari, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Maler der Grabkammer der Nefertari 003 / Maler der Grabkammer der Nefertari, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

As a translation of hand gestures onto a flat surface, picture-making has a clear link to writing, and, in fact, led to the development of writing (this is obvious in Egyptian hieroglyphics). And writing, of course, reduces life into a scratchy shorthand for bookkeeping and chronicling. It is a utilitarian short-cut that greases the wheels of civilization and speeds communication across time and space. Ancient pictures often participated in this “writerly” identity—they were a humble means to an end. Religious honor was reserved, meanwhile, for the more stately idol form.

This all changed with the Christian icon. In a few short centuries, the Christian icon (from the Greek “eikon” for “picture”) supplanted the grand statue as the main devotional object across Europe, Asia Minor, and the Mediterranean. From there, the icon—showing sainted figures in golden heavens—eventually spread to the rest of the world. Today, our idea of a “profound artwork” is best embodied by the descendants of these icons. The world’s most famous artworks, in fact, are almost all pictures. And our most celebrated artists—men like Claude Monet, Leonardo da Vinci, and Vincent van Gogh—were all picture makers of unique, iconic power.

![]() Icon with the Archangel Michael (14th cent.) at the Byzantine and Christian Museum on 12 April 2019 / George E. Koronaios, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Icon with the Archangel Michael (14th cent.) at the Byzantine and Christian Museum on 12 April 2019 / George E. Koronaios, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

So, why did Christians favor the picture over the more monumental sculpture? And why did this form meet with so much global success?

The humble, flat picture, it turned out, was well-suited to express the spiritual paradoxes discovered by early Christianity. Christianity teaches of one God vaster than the universe. But simultaneously, it proclaims a God that took human form. Christianity banished the old gods, affirmed the philosophers’ highest ideals, and also asserted the preciousness of all Creation. The picture captured these tensions between the celestial and the down-to-earth.

First, of course, the picture avoided idolatrous associations with sculpture (sculpted, “graven images”). Second, it had the benefits of cheapness and portability, and could make faith more personal, foreshadowing photographs of loved ones. And third, as a humble “short-hand,” the icon avoided a sense of completeness. In its smallness and flatness, it was more like an abstract symbol than a “graven image,” with the latter’s connotations of total, three-dimensional resemblance. The icon captured the paradox of the finite-yet-infinite Christ. Its incompleteness made space for the truly transcendent.

Notably, all of the qualities that distinguished the earliest Christian icons still characterize our most beloved pictures today—even if those pictures don’t have explicitly religious connotations. Vincent van Gogh’s Starry Night, for example, potently evokes a spiritual reality without seeming to BE a spiritual reality, as an idol would. The same is true of Rembrandt’s portraits or Raphael’s Madonnas. These images thread the same needle threaded by the earliest icons: evoking, but not quite capturing, as they usher the soul to a higher place.

Raffaello Sanzio - Madonna Sistina / Raphael, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Raffaello Sanzio - Madonna Sistina / Raphael, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

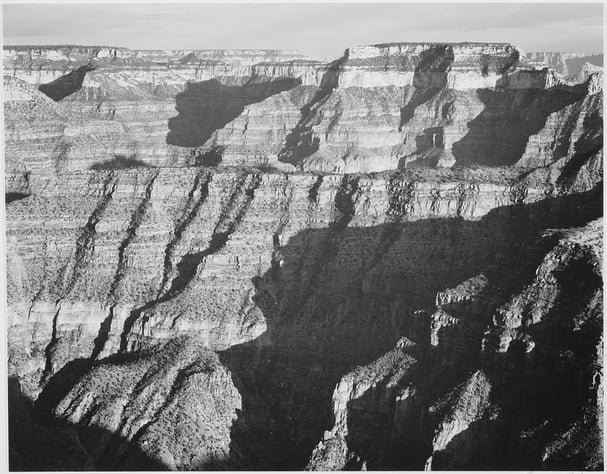

Today, our world is overrun by pictures with exactly these qualities. Transcendent, “iconic” images of landscapes, celebrities, beautiful women, and noble beasts stare out from magazines, televisions, and computer screens. Like Christian icons, these images do not embody divinity so much as they suggest some mysterious transcendence we long for—hinted at through a beautiful, yet fleeting form.

Ansel Adams - National Archives / Ansel Adams, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Ansel Adams - National Archives / Ansel Adams, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

The worldwide domination of “icons” attests, I think, to a deeply-felt spiritual need, even in the most secular of cultures—it is evident from Tokyo to Times Square, from Abu Dhabi to St. Petersburg. In fact, starting in the early twentieth century, it has been commonplace among cultural elites to dub art museums the new “temples” of the soul. Meanwhile, on platforms like Instagram, we labor to present images of ourselves that are often factually “false,” but on a deeper level, “true.” They are the selves we wish to be—selves foreshadowing (perhaps) a heavenly fulfillment, just as the earliest icons did.

1 times square night 2013 / chensiyuan, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

1 times square night 2013 / chensiyuan, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Thus, our image-saturated culture is, in some ways, one of the most spiritual to have ever existed. It is a culture that grasps desperately and constantly for the ineffable and high. Yet, we are without a framework or clear ideals, and without a sense of holiness or true humility. We are marked by unmoored reaching and eccentric intuitions—by a billion private heavens with solitary gods.

Interior view—Blanton Museum of Art—Austin, Texas / Daderot, CC0 via Wikimedia Commons