As a neuroscientist conducting research at an Ivy League-affiliated hospital, some might assume that I have an irredeemably hostile regard for historical paradigms on human nature. After all, there is an unfortunate tendency for contemporary scientists to disregard, or even scorn, pre-modern and ancient philosophical reflections. However, this would be a gross error in supposition and judgment.

Functional Structure and the Philosopher

For the past several years, I have been working energetically to decode the human connectome; or, in other words, to make scientific sense out of the wildly complex wiring diagram of the human brain.

It has been said that the human brain is the most complex physical system in the known universe. This popular assertion seems to be correct. In fact, the wild complexity of the human brain’s wiring diagram is itself one of the principal features that drew me toward it as a deliciously interesting problem that was worth trying to solve.

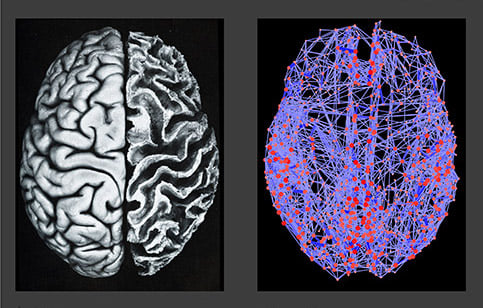

Brain anatomy (left) and connectome (right) / © 2008 Hagmann et al

Brain anatomy (left) and connectome (right) / © 2008 Hagmann et al

In 2017, when my colleagues and I published an architectural decomposition of the human brain’s functional patterns, none of us knew the astounding correlations that would emerge from one of the most unexpected of places: namely, from Aristotle’s philosophy of the human soul.

As my colleagues and I converged on a mathematically sound solution for the fundamental components of the brain’s hierarchical organization, it became apparent to us that the three principal constituents of typical brain function in humans are composed of (in order) the following: primary sensorimotor networks, the so-called default mode network (responsible for mental simulation), and an array of networks that are correlated with fluid intelligence (Ferguson, 2017).

We were satisfied with this empirically-founded description of the brain’s functional architecture, and so were our reviewers and our editor. A year later, though, Aristotle—referred to affectionately by Thomas Aquinas as “The Philosopher”—would blow the lid off of the implications for our work.

Hylomorphism and the connectome

I honestly don’t remember why I was originally drawn to Aristotle’s treatise on the philosophy of soul, which is most commonly recognized by its Latin title, “De Anima,” but drawn I was. As I waded into the then foreign waters of Aristotle’s theory of soul, I started to realize that my colleagues and I had been scooped by a Greek contemplative who lived two millennia before the first brain imaging technology was ever invented.

In “De Anima,” The Philosopher lays out a biological perspective of the human soul, rather than the fatally problematic notion of a Cartesian or Platonic spiritual dualism. Instead of conceptualizing the human soul as a ghostly substance that can be isolated from the human body, Aristotle asserts that “soul” is the form of the body—a deceptively simple hypothesis known by the technical term “hylomorphism” (a Greek compound word literally meaning “matter and form”). He further explains the human soul as an interlocking system of functional networks that are represented in human physiology.

Already, this was beginning to sound like our general framework for understanding the human connectome. More specifically, Aristotle identifies sensory faculties in the human soul giving rise to memory and imagination, which give rise to intellective faculties, which in turn exercise top-down control on appetitive faculties.

The precise one-to-one correlation between our set of connectome components and Aristotle’s set of soul faculties struck me with an awe-inspiring lightning bolt. The Philosopher’s model of a sensitive to imaginative to intellective functional axis is exactly what we had seen in our neurobiological solution set of primary sensory network, default mode network, and intelligence network configurations.

What else does Aristotle get right?

The natural question that arose in my mind was, “What else does Aristotle’s philosophy get right?” This is exactly the question that I currently chase in my work. Fortunately, I have found a sympathetic team of colleagues from academic trainings that span medicine, neuroscience, and philosophy.

Under the banner heading of “Soul and Brain,” we have created an exciting initiative that aims to chart the convergence between philosophy of soul and neuroscience in a rigorously interdisciplinary manner. To learn more, see our one day event, “Soul and Brain, Live,” which will take place in Boston on August 3, 2019.

Only hard work and time will tell us for certain whether we are chasing anachronistic rabbits or whether there is a wealth of astonishing discovery ahead of us. But as for me and my intellectual peers, we are hedging our bets generously on the eventual triumph of the human Soul.

References: Ferguson, M. A., Anderson, J. S., & Spreng, R. N. (2017). Fluid and flexible minds: Intelligence reflects synchrony in the brain’s intrinsic network architecture. Network Neuroscience, 1(2), 192-207. Reeve, C. D. C. (2017). De anima. Hackett Publishing.

Read Also:

Hard-Wired for Faith: The Religious Experience and the Brain