One evening at the dawn of the twentieth century in the Kingdom of Poland, a ten-year-old boy named Raymond prayed to the Mother of God, asking her what kind of man he was to be. In answer to his prayer, Mary appeared to him later that night, holding two crowns. Mary, who had seen her own divine Son accept a crown of thorns, held out two crowns to this young man. The first crown was white, which signified virginity; the second crown was red, signifying martyrdom. Mary asked Raymond if he were willing to accept either crown.

The young man’s answer was breathtaking: “I choose both.”

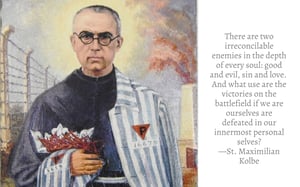

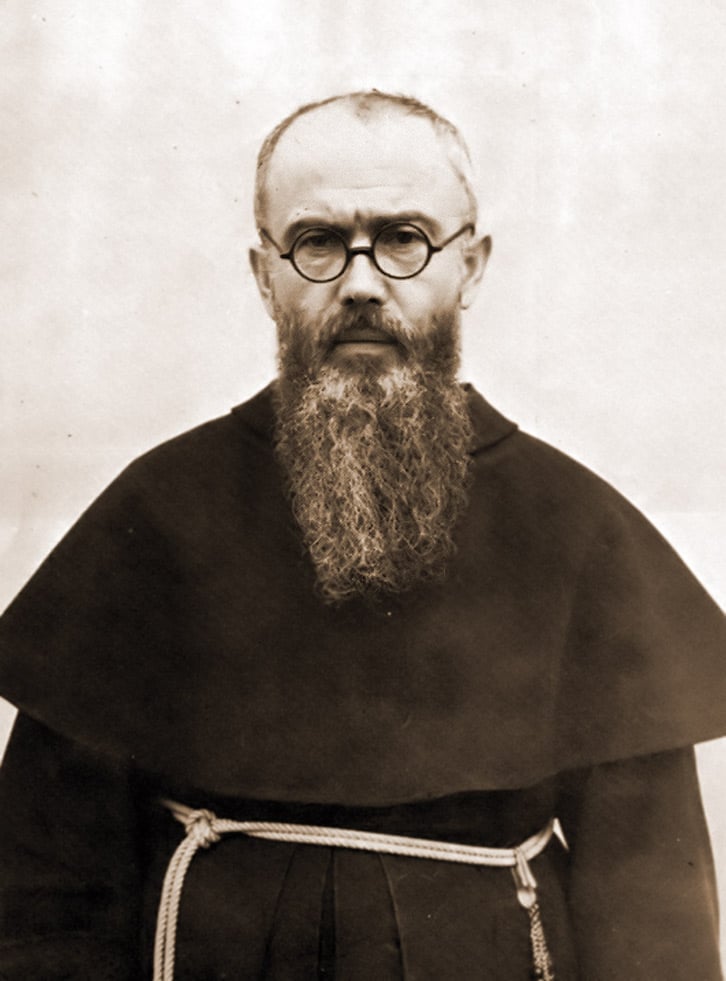

This little boy grew up to be known by the Nazis at Auschwitz as Prisoner 16670. He is known to the choirs of heaven as Saint Maximilian Kolbe.

Early life

Born in 1894, Raymond (later taking the religious name Maximilian), was the second of five boys to Julius and Maria Kolbe—parents who were devout Catholics with a devotion to the Blessed Mother.

Their son Raymond was a boisterous boy, and his mother blurted to him one day, “Whatever kind of man will you grow up to be?” Raymond wondered the same thing about himself, and that is when he asked Mary—in prayer—this most important interrogative. After this encounter with Mary, Raymond’s demeanor changed significantly: less playful, but increasingly joyful as he came to realize his mission and calling.

Raymond exhibited a strong intellect, as he excelled in school and soon became an informal tutor to his young classmates. As a teenager in a Franciscan seminary school, Raymond again impressed his teachers with comprehension of science, physics, and mathematics. Again, in the seminary, he exhibited a powerful mind.

Upon entering the Franciscan novitiate in 1910, Raymond was given the new name “Maximilian,” as a reminder that he was dying to his old self and “putting on the new man,” as referenced in Ephesians. As part of his priestly formation in the years that followed, Kolbe obtained a doctorate in philosophy from the Pontifical Gregorian University followed by a doctorate in theology at the Pontifical University of St. Bonaventure.

In 1918, Maximilian Kolbe was ordained a priest. As Our Lady of Fatima had assured the seers in Portugal, World War I was coming to a close.

But a new war was only beginning.

The world between the wars

Militia of the Immaculata

In 1917—while still studying for his second doctorate in Rome—Kolbe founded the Militia of the Immaculata (MI), which sought to combat the errors of Freemasonry and to win souls for Christ through Mary. The MI quickly experienced far-reaching and miraculous success. Its first meeting in 1917 had seven attendees; three years later, its membership rose to over four hundred members; by the beginning of World War II, the organization had more than five hundred thousand members.

Perhaps even more impressively, the organization’s magazine, Knight of the Immaculata, (which is still in print) had a publication run of roughly one million. (For some perspective, that is about four times more than the current paid subscription to The Washington Post). In addition to this magazine, Kolbe produced a radio show and wrote pamphlets and books, making his impact in Poland profound.

Kolbe founds Niepokalanow

In 1927, in order to serve the needs of the growing organization, Father Kolbe located a six-acre piece of land west of Warsaw that he thought would work perfectly. Since the land was owned by a prince who desired some recompense for the property, Father Kolbe put a statue of Mary on the land and said a little prayer, “Take possession of this land, for I know it is just what you want.” The prince gave Father Kolbe the property.

When the Franciscan friars came to the land, the Polish people welcomed their new neighbors by bringing food and lending a hand in the construction of the new location. Soon enough, the tiny Franciscan town was complete. Called Niepokalanow (City of the Immaculate), the tiny town of little huts, seminary, chapel, and printing facilities was modest in stature, but spectacular in intention, as this was meant to be the headquarters to win the world’s souls for Mary.

Never tiring of speaking about his love for Mary, Father Kolbe may have encountered those who questioned if he loved Mary perhaps too much. And so he assured them,

“Never be afraid of loving the Blessed Virgin too much. You can never love her more than Jesus did.” -St. Maximilian Kolbe

Kolbe travels to Japan

Three years later, Kolbe turned his attention to the Pacific Rim, where he lamented that so few of the Japanese people had embraced Christianity. Accompanied by a few fellow Franciscans, Father Kolbe went there and founded a similar little city near Nagasaki. He was unable to stay longer since his long bout with tuberculosis was getting worse. In 1936, he returned to his native Poland and to Niepokalanow, which had grown exponentially in these years.

Fr. Maximilian Kolbe in 1936

Fr. Maximilian Kolbe in 1936

To the lament of mankind, however, another force had also grown stronger in Europe—the Nazi Party. And it had its evil eyes set squarely not only on Poland broadly, but on Niepokalanow.

No greater love

By 1938, Father Kolbe was presciently convinced that the Nazis were going to seize Poland. As the Nazis approached in 1939, Father Kolbe sent away almost all the friars, but Father Kolbe chose to stay behind with three dozen friars, and Niepokalanow was essentially converted to a hospital for wounded Polish soldiers.

The Nazis arrive in Poland

The Nazis rolled their tanks into Poland on Sept. 1 and the town of Niepokalanow was bombed on Sept. 7. Yet Father Kolbe remained in place. Not only that, but with the Nazis figuratively, if not almost literally, breathing down his neck, he continued to publish materials critical of the Nazis.

The Nazis had seen enough of his writings that illustrated the evils and lies of Nazism, and on February 17, 1941, Father Kolbe was picked up and arrested. On May 28, he was sent to his final earthly destination: Auschwitz.

Life and death at Auschwitz

Once in Auschwitz, the forty-seven year old priest—who had suffered from tuberculosis for two decades—was given extra work. (Catholic priests were specifically treated with additional hostility by the Nazis.)

One day, in an event of remarkable similarity to the Passion of Christ, Father Kolbe was ordered to carry wooden logs but fell under their weight, only to be severely beaten by the guards as he lay on the ground. He was then given fifty lashes and thrown into the woods to die. Yet, he did not die.

Instead, he was carried to the infirmary where, in clear violation of Nazi regulations, he heard Confessions of the sick and suffering. The survivors at Auschwitz later attested to Kolbe’s tender love for his fellow prisoners and his generosity, which even included giving away the tiny portions of soup and food allotted to him.

In July, the Nazis discovered that a man had escaped. The Nazis had a procedure for punishing the remaining prisoners after an escape: ten men would be starved to death. A German officer named Karl Fritsch gleefully chose the ten men who were standing in ranks. When one of these men, Franciszek Gajowniczek, pleaded, “My wife and children,” Father Maximilian Kolbe broke ranks and made a plea of his own: “I am a Catholic priest. I want to die for that man; I am old; he has a wife and children.”

Father Kolbe’s dying wish was granted, and he was led away to die naked in a dark cellar. But if the Nazis were expecting to hear cries of sorrow and anguish, they were sorely disappointed. Because as Kolbe awaited a crown that was promised four decades prior, a somewhat unexpected sound was heard from his cell: singing. Maximilian Kolbe was heard singing Marian hymns in honor of his Immaculate Queen.

Two weeks later, the Nazis again had seen and heard enough. Father Kolbe had not succumbed to starvation, so he was injected with a fatal dose of phenol on August 14. The Feast of the Assumption was the next day, but this one was extraordinary. Because while Catholics across the world celebrated Mary’s entrance into Heaven, Father Maximilian Maria Kolbe had entered Heaven himself, and this time, he would celebrate it with his Heavenly Mother in person.

A victory over hate

Pope John Paul II proclaimed that Maximilian Kolbe was the patron saint of the 20th century. If he has something to teach the 20th century, he certainly has much to teach us now, as the 21st century seems eager to embrace the errors of yesteryear. In his canonization homily, Pope John Paul II said,

“The death of Maximilian Kolbe became a sign of victory. This was victory won over all systematic contempt and hate for man and for what is divine in man—a victory like that won by our Lord Jesus Christ on Calvary.” -Pope John Paul II

Maximilan Kolbe shows us that resistance to evil is a consequence of love, rather than the contrary. Moreover, if we are lacking in love, we can offer little resistance to hate. In our world twisted with racism and hatred and religious persecution, the life and death of Father Maximilian Maria Kolbe provides an unmistakable answer to those who wish to resist evil forces and influences. As we fight against a culture of death and hate, we must turn to Mary. That is the enduring lesson of Maximilian Kolbe.

Interested to learn more about life during the Nazi occupation, and why we should never forget what happened during the Holocaust? Read our free ebook about a Jewish boy who escaped the Nazis at age 5. Download your copy below.

Read Also: